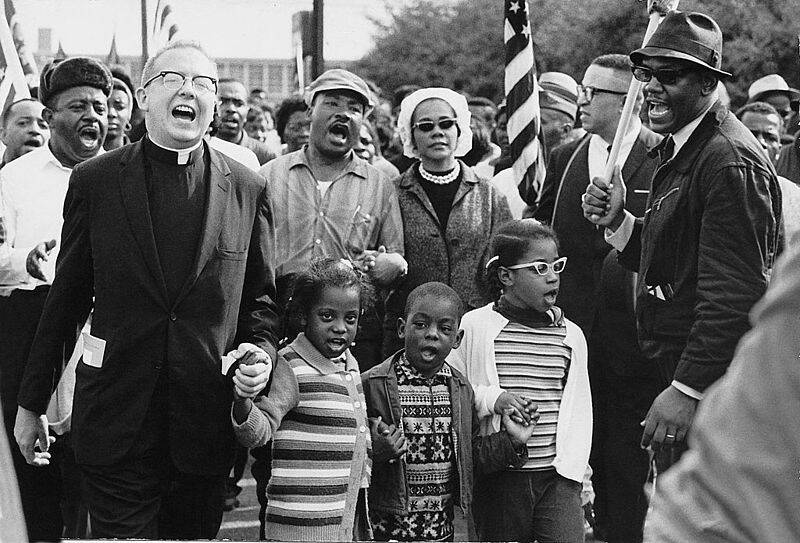

Getty Images African Americans, led by Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., line up in front of the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama to register to vote.

With the South’s defeat at the end of the American Civil War, Black men were given the right to vote for the first time in the nation’s history in 1870, and the addition of their voices in the electoral process was set to change the course of American history.

During the Reconstruction period that followed the war, enfranchised Black men gave Ulysses S. Grant his narrow victory in the popular vote. Before that period ended, 2,000 Black Americans would be elected to office in the South.

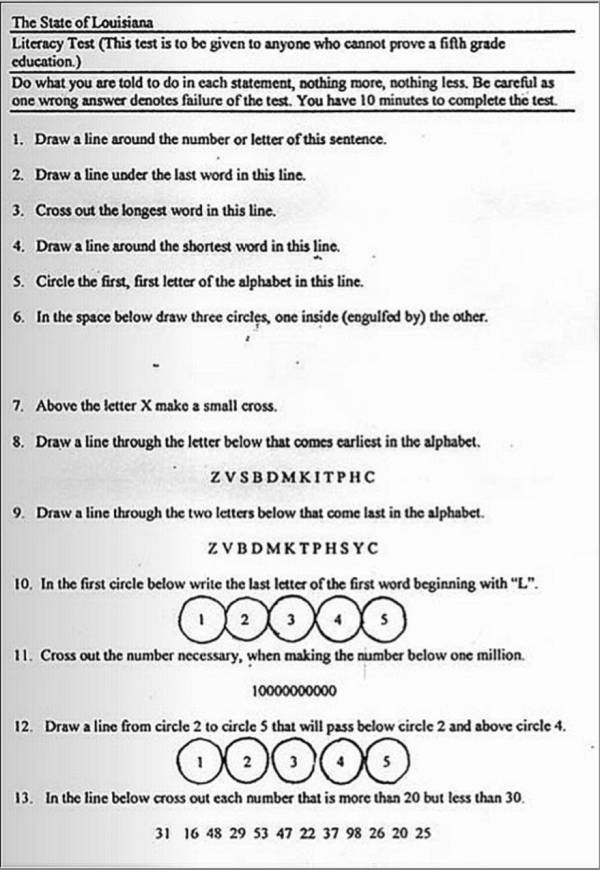

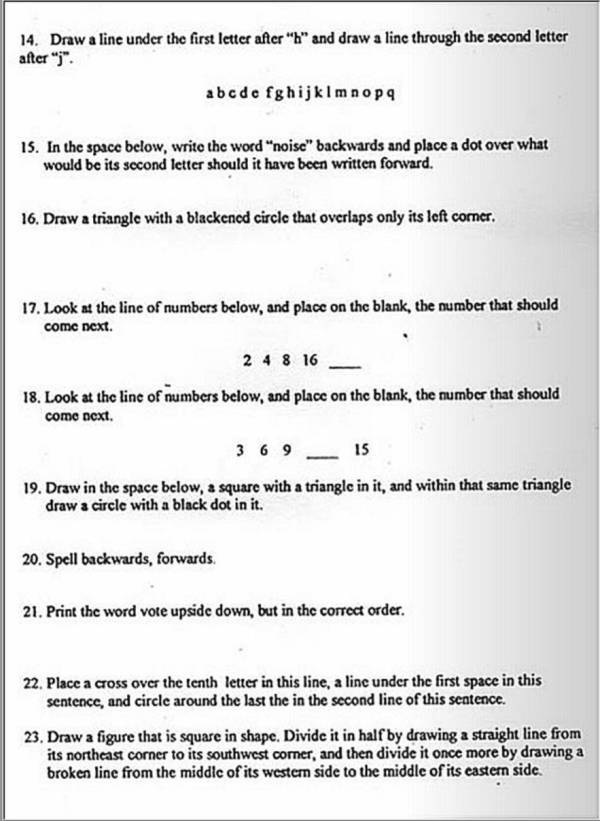

But by the dawn of the 20th century, all the progress that was made to expand the rights of formerly enslaved Black Americans was severely crippled by the institution of state-specific voting laws that were designed to exclude Black voters from the ballot box. Southern states created elaborate voter registration procedures or “voting literacy tests” that determined whether the voter in question was literate enough to cast their ballot.

Of course, these voting literacy tests were administered largely to voters of color and were scored by biased judges. The tests were intentionally confusing and difficult and one wrong answer meant a failing grade. Even Black voters with college degrees were given failing scores.

While these voting literacy tests were made unconstitutional in 1965, some laws still exist that prevent Americans from casting their vote.

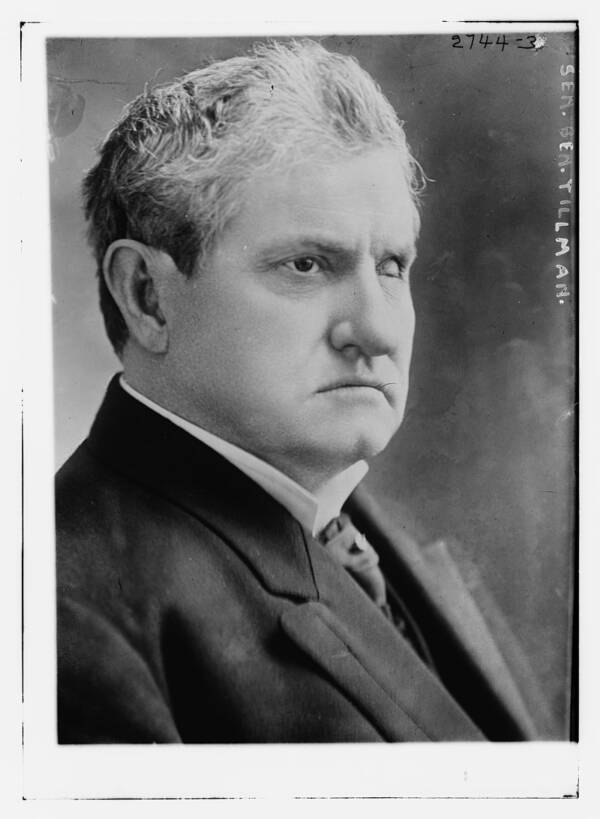

Wikimedia Commons “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman was a senator and a governor who worked to uphold white supremacy in South Carolina.

In the wake of the Civil War, there came a wave of opposition against the rights of freed slaves in the South and even in the North, which led to a series of racist legislation known as Jim Crow laws. These laws legalized segregation throughout the country in an effort to reinstate white supremacy.

In the South, self-proclaimed “Redeemers,” who were white men and women committed to resurrecting the white supremacist power dynamic that had existed in the Antebellum South before Reconstruction, even espoused acts of terrorism and lynching to prevent Black Americans from exercising their rights.

As Ben Tillman, a turn-of-the-century governor and senator of South Carolina, put it: “Nothing but bloodshed and a good deal of it could answer the purpose of redeeming the state from Negro and carpetbag rule.”

Jim Crow voting laws were also passed throughout the states in an effort to keep African Americans from the polls. These laws included poll taxes and literacy tests that were impossible for uneducated free slaves to pass.

Officially, states could present literacy tests to voters of any race who were unable to provide proof that they’d attained an education beyond a fifth-grade level. But it quickly became obvious that these tests were disproportionately administered to Black voters — and were made virtually impassable.

Was The Trojan Horse Real? Inside The Historical Debate

By All That's Interesting

13 Incredible Archaeological Discoveries From 2021 That Made Us See The World Differently

By All That's Interesting

The Mythical Kandahar Giant, The Biblical Cryptid Allegedly Killed By U.S. Special Forces In Afghanistan

By All That's Interesting

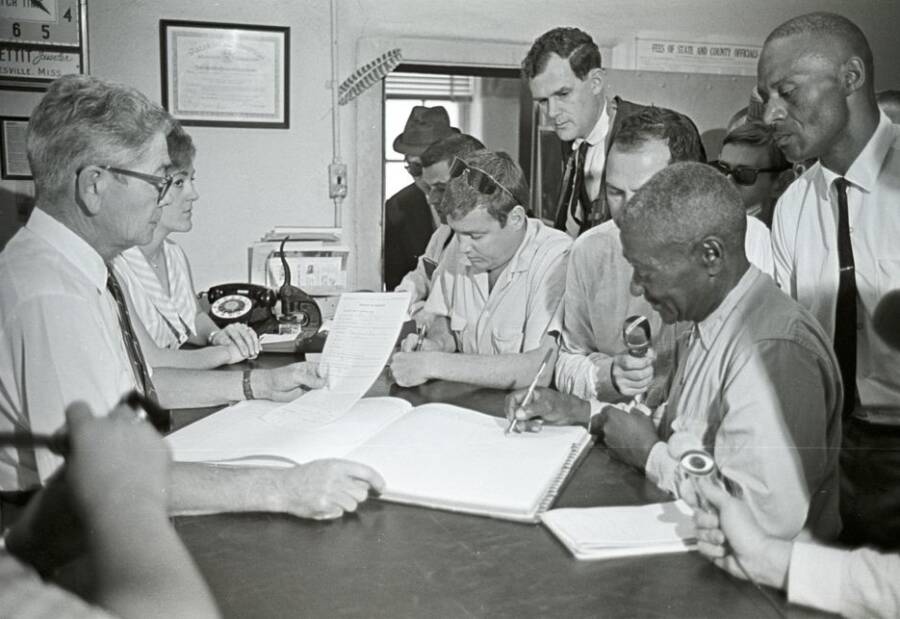

Stanford University Library An elderly Black man registers to vote in Batesville, Mississippi, 1966.

In the mid-1960s, a professor of law at Duke University, William W. Van Alstyne, conducted an experiment in which he submitted four questions found on the Alabama voter’s literacy test to “all professors currently teaching constitutional law in American law schools.”

Alstyne’s professors were told to answer all submitted questions without the aid of any external reference, just as any voter would be required to do when presented with the test. Ninety-six respondents sent Alstyne their answers; 70 percent of the answers given to him were incorrect.

Professor Alstyne concluded, “Presumably, these men, each of whom teaches constitutional law, each having at least 20 years of formal education, are no less ‘qualified’ by literacy than those in Alabama to whom this type of test is supposed to apply.”

Former North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Henry Frye recounts an experience he had in 1956 that, historically, has been experienced by many Black Americans: being denied the right to vote.

As Alstyne had demonstrated, passing a voting literacy test was virtually impossible. The questions were intentionally written to confuse the reader, and one wrong answer would result in automatic failure.

In practice, a white registrar would administer and grade the tests. These registrars would be the arbiters of who passed and who failed, and more often than not, a registrar would simply mark answers wrong for no reason.

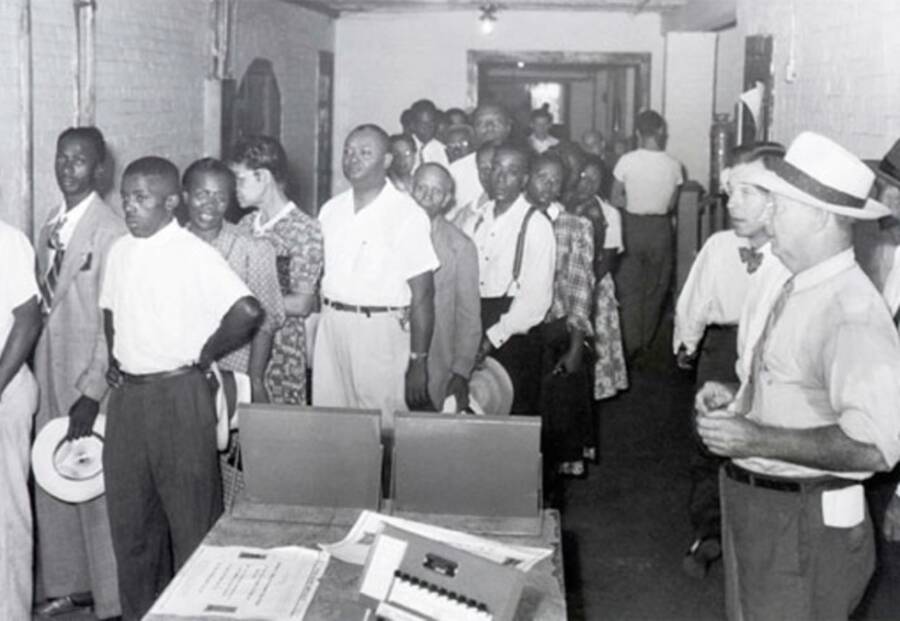

Getty Images Black voters go to the polls in South Carolina, for the first time since the Reconstruction era, after the Supreme Court ruled they could not be deprived of the right to vote, Aug. 11, 1948.

These literacy tests were usually composed of about 30 questions and had to be taken in 10 minutes. The tests varied by state; some focused on citizenship and laws, others on “logic.”

For example, one of the tests from Alabama focused heavily on civic procedure, with questions like “Name the attorney general of the United States” and “Can you be imprisoned, under Alabama law, for a debt?”

In Georgia, questions were more state-specific; “If the Governor of Georgia dies, who succeeds him and if both the Governor and the person who succeeds him die, who exercises the executive power?” or “Who is the Georgia Commissioner of Agriculture?”

Of all the states, Louisiana’s test was, by far, the most incomprehensible. There were no questions about the state’s inner workings or the country’s. Instead, a voter was presented with 30 questions so convoluted and nonsensical that it’s easy to imagine they were cooked up by one of the more malicious characters in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Here follows Louisiana’s 1964 literacy test:

Following the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which finally recognized racial segregation in public schools as unconstitutional, an emboldened Black populace made tremendous strides to undoing racist Jim Crow laws. Succeeding years saw the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1964. After centuries of struggle, the prospect of true racial equality in America seemed to be within striking distance.

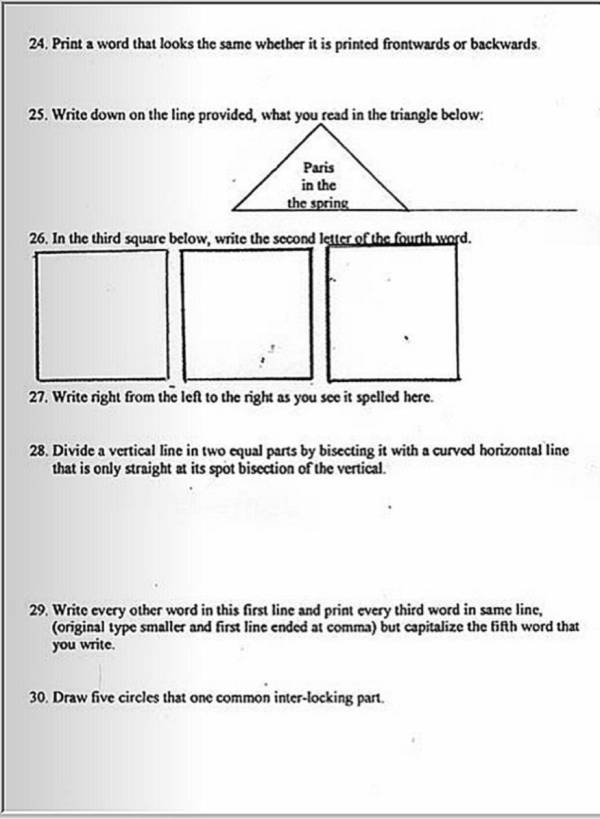

Tensions reached a fevered pitch when on March 7, 1965, Black activist John Lewis led a non-violent army of about 600 marchers out of Selma, Alabama and over the Edmund Pettus Bridge. They had come to protest discriminatory voting tests and demand that Black Americans in Alabama be allowed to freely exercise their right to vote.

At the bridge, protesters were met with a violent and brutal response from local police on what came to be known as Bloody Sunday. In the two days that followed, 80 U.S. cities held demonstrations in solidarity with Selma’s protesters.

Wikimedia Commons Civil Rights Movement Co-Founder Dr. Ralph David Abernathy is joined by his three children along with Martin Luther King Jr., Corretta Scott King, and James Joseph Reeb as they march from Selma to Montgomery in the spring of 1965.

But it wasn’t until the death of white minister James Joseph Reeb, who had taken part in one of the Selma marches and days later was found killed by a group of white men — all of whom were later acquitted — that tensions finally reached their breaking point. With the death of Reeb, white America was finally galvanized into taking real action to stop voting discrimination against Black Americans.

As the end of that summer drew near, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law and the shape of American political life was changed forever. Not only did the new law forbid the use of literacy tests and poll taxes, but Section five of the law also prevented several states, those which had historically been the most flagrant obstructers of the Black vote, from concocting any new methods for electoral sabotage.

Wikimedia Commons Martin Luther King Junior reaches out to take the hand of President Johnson after he signs the Voting Rights Act into law on Aug. 6, 1965.

The impact of the Voting Rights Acts was dramatic.

Three years after its passage, Black registration in Mississippi exploded from seven percent to 54 percent. Since its passage, the Voting Rights Act has prevented over 700 legislative attempts at voter discrimination. Originally set to expire after five years, the act has instead been continuously renewed since its inception and, after its latest renewal in 2007, is scheduled to last until August of 2032.

But as Black voter turnout reached newfound peaks in 2008 and 2012, delivering America’s first black president to the White House on both occasions, a reinvigorated campaign to suppress the Black vote has emerged.

Since 2010, a wave of voter restrictions has been released by the Republican Party, all drafted with the specific intent of suppressing minority voting. The excuse given by those promoting such measures is to prevent voter fraud. This is presented as a serious argument, in spite of the fact that an exhaustive Loyola Law School study found that, after reviewing one billion instances of American voting from 2000 to 2014, only 31 out of that billion were instances of in-person voter fraud.

Getty Images A group of voters line up outside the polling station, a Sugar Shack small store, in Peachtree, Alabama, after the Voting Rights Act was passed the previous year. May 1966.

In 2013, with a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court determined that the metrics used to decide which states should be subjected to Section five’s oversights were both outdated and unconstitutional. Weeks after the ruling, North Carolina passed H.B. 589, a law that instantly rolled back 15 years’ worth of victories for voters’ rights. Sixteen other states followed suit, passing similar laws designed to suppress minority voting.

As the 21st century continues to unfold, a new set of legislative tools now empowers a fresh wave of 21st century “Redeemers” to achieve the dream laid out by their predecessors: the preservation of white hegemony and the suppression of Black voting power.

After this look at the history of voting literacy tests, have a look some of the most powerful photos from the Civil Rights movement. Then, read about Ida B. Wells, a pioneering civil rights hero.